How to Overcome a Pedagogy of Poverty

By: Steve Ventura

The Pedagogy of Poverty

In 1991, Martin Haberman coined a phrase designed to address what many struggling learners experience in classrooms across the United States. Haberman identified specific instructional strategies as “the pedagogy of poverty,” because those practices were heavily geared towards giving information and controlling behavior rather than creating optimum classroom environments where students identify questions, make meaning and solve problems. Haberman went on to describe that many teachers are not adequately prepared by teacher education programs to change the pedagogy of poverty observed in so many schools. Many times, the teachers’ own schooling experiences also reflected this kind of instruction. Haberman observed that teachers frequently experience professional development that affirms such instruction, "with facilitation that fails to support them as engaged, curious, autonomous professionals." (Haberman 1991) Not surprisingly, different studies contained similar findings. Dougherty and Barth have observed, "poor and minority children are systematically bludgeoned into low academic performance with a steady dose of low-level, boring, if not downright silly assignments and curricula." (1997) The teaching acts that Haberman defined explicitly as the "pedagogy of poverty" are:

- Giving information

- Asking questions

- Giving directions

- Making assignments

- Monitoring seatwork

- Reviewing assignments

- Giving tests

- Reviewing tests

- Assigning homework

- Reviewing homework

- Settling disputes

- Punishing noncompliance

- Marking papers

- Giving grades

Needless to say, many of these practices are still embedded in schools and districts across the country. The date of the original study is irrelevant because this was the type of teaching observed in the 1990s and it is still being practiced today. Thus, the achievement gap has not closed as much as we would like.

It is important to note that most teachers do not intentionally deliver ineffective instruction. However, it would be academic malpractice to ignore the fact that certain assignments are given and they are simply not worth doing. Students cannot learn when they are denied the type of instruction that they deserve, as highly effective instruction is a moral and ethical obligation.

A Pedagogy of Prosperity

Perhaps John Hattie captures how we must use our instructional time wisely. "Our time with students is limited and valuable. Every minute we spend with them should be spent using the practices that are most likely to be successful. This requires us to shift our perspective from looking at instructional practices that work to looking at practices that work best" (Hattie 2009).

A pedagogy of prosperity is both a mindset and a set of highly effective practices. It means that teachers and leaders see the potential in every student and a belief to help all students become active, engaged learners.

Four Principles of Effective Instruction

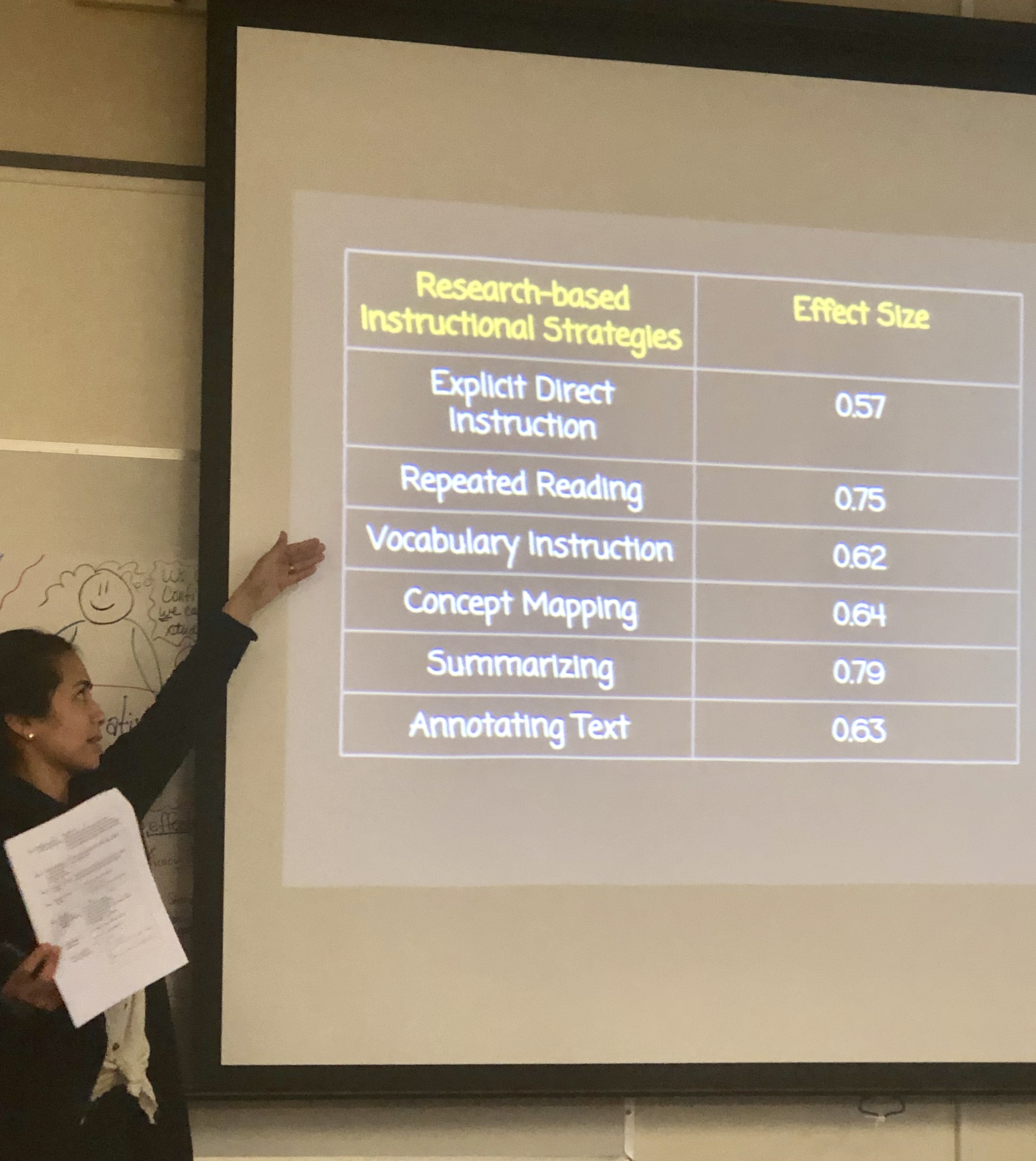

The work of researchers over the years suggest that there are practices of teaching that have an incredibly high probability of making a difference in the classroom, and they have been proven effective regardless of home life, demographics and socio-economic status.

1. Teacher Clarity is clear about what to teach and how to teach it. (Hattie 2010) Teacher Clarity is an effect than can help schools and districts move away from random lesson planning by clarifying instruction through the use of learning intentions, success criteria, and learning progressions. With a notable effect size of .75, teacher clarity has the potential to dramatically increase student achievement. But what does teacher clarity actually look like in practice? Educators use words like “program” or “system” because those terms are easy to understand. Teacher clarity is neither a program or system. It is a framework built on collaborative philosophies and explicit instruction.

1. Teacher Clarity is clear about what to teach and how to teach it. (Hattie 2010) Teacher Clarity is an effect than can help schools and districts move away from random lesson planning by clarifying instruction through the use of learning intentions, success criteria, and learning progressions. With a notable effect size of .75, teacher clarity has the potential to dramatically increase student achievement. But what does teacher clarity actually look like in practice? Educators use words like “program” or “system” because those terms are easy to understand. Teacher clarity is neither a program or system. It is a framework built on collaborative philosophies and explicit instruction.

2. The purpose of feedback is to close the gap in a student’s learning. To effectively close the gap, teachers need to communicate the intended goal (or “learning intention”) to the student. Once specific learning intentions are listed, it is critical that we list the success criteria, especially so students can self-assess themselves. A prerequisite for giving effective feedback is having clear learning intentions and success criteria.

3. Formative Assessment and Evaluation. A significant argument throughout John Hattie’s Visible Learning is the power of feedback to teachers so that they can determine if they are achieving the learning intentions created for students. The major message is for teachers to pay attention to the formative effects of their teaching, which include short-cycle formative assessments and other indicators designed to assess the effects of their instruction. Formative assessment informs the practice of teachers, promotes equity for all students, build’s capacity of all team members, provides an effective strategy to determine if learning intentions have been achieved and offers a powerful tool to appropriate new knowledge about teaching and learning.

4. High-functioning classrooms elevate the use of questioning and student dialogue. Questions are more important than answers, but in most classrooms, it is the answers that have greater emphasis. Teach students how to answer this simple question: What do you do when you don’t know what to do? Having students think through the use of metacognitive strategies helps to develop self-regulated learners who are able to monitor their own learning, rather than depend on the teacher for all of their needs. Remember, student engagement is a product of effective instruction.

We all want students to be engaged by teachers and leaders who can activate learning, using academic language, challenge and equitable practice. This means that teachers need assistance in learning how to do this as well. A pedagogy of prosperity means better-equipped teachers to provide support to all students, especially our most underserved. “The research shows that schools can reach all students when districts, schools, and teachers marry powerful and proven instructional strategies, support for student learning and social-emotional needs, wraparound services, and support for teacher collaboration and learning...we can create systems in which deeper learning is equitably accomplished.” (Noguera, Darling-Hammond & Friedlaender)

References

Clarke, Shirley. 2005. Formative Assessment in Action: Weaving the Elements Together. London: Hodder Murray.

Dougherty, E. & P. Barth. “How to Close the Achievement Gap.” Education Week, April 2, 1997.

Haberman, Martin. 1991. “The Pedagogy of Poverty Versus Good Teaching.” Phi Delta Kappan. 73, no. 4: 290-294. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/jff-report-equal-opportunity-deeper-learning.pdf

Hattie, John. 2009. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge.

Hattie, John. 2011. Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximising Impact on Learning. London: Routledge.

Noguera, Pedro, Linda Darling-Hammond, & Diane Friedlaender. 2015. Equal Opportunity for Deeper Learning. Students at the Center: Deeper Learning Research Series. Boston, MA: Jobs for the Future. https://studentsatthecenterhub.org/resource/equal-opportunity-for-deeper-learning/